I was struck by this recent observation from Timothy Clark in his HBR article on cultivating “Intellectual Bravery”:

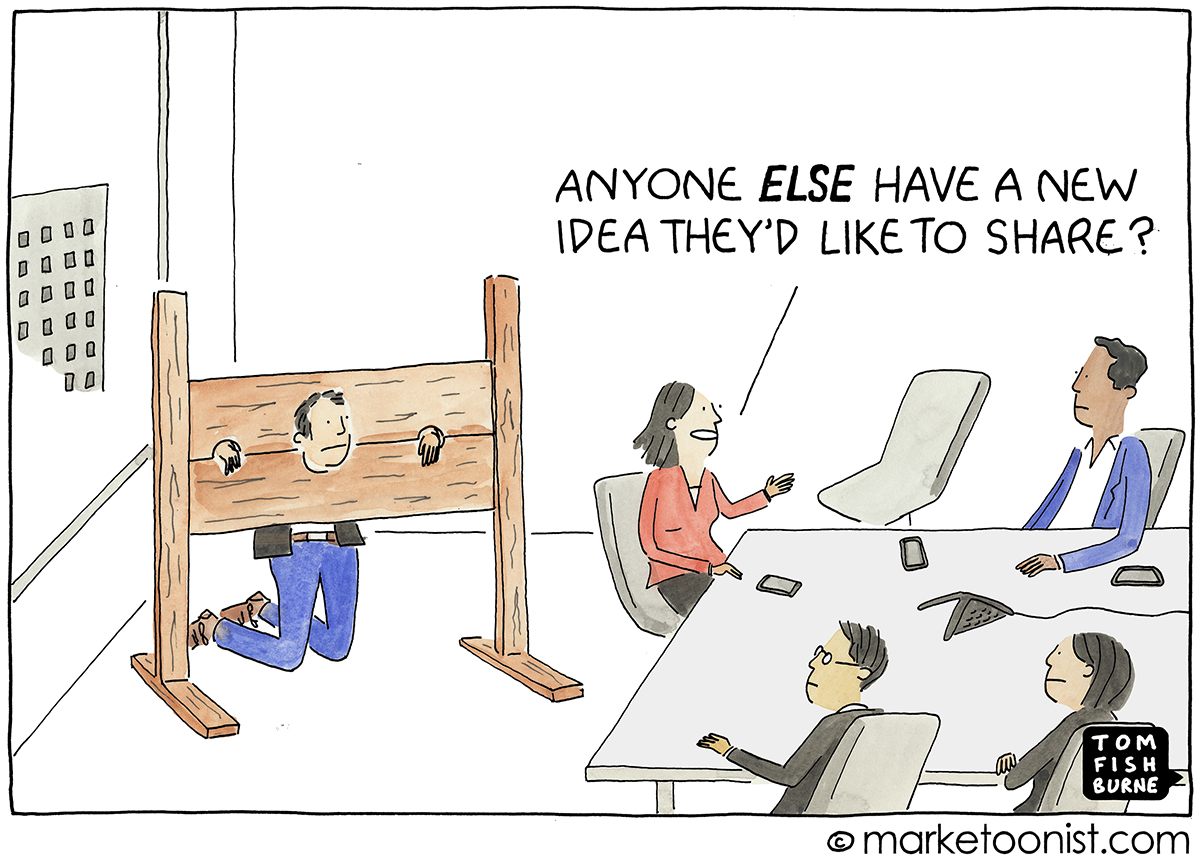

“Intellectual bravery is a willingness to disagree, dissent, or challenge the status quo in a setting of social risk in which you could be embarrassed, marginalized, or punished in some way. When intellectual bravery disappears, organizations develop patterns of willful blindness. Bureaucracy buries boldness. Efficiency crushes creativity. From there, the status quo calcifies and stagnation sets in.

“The responsibility for creating a culture of intellectual bravery lies in leadership. As a leader, you set the tone, create the vibe, and define the prevailing norms. Whether or not your company has a culture of intellectual bravery depends on your ability to establish a pattern of rewarded rather than punished vulnerability.”

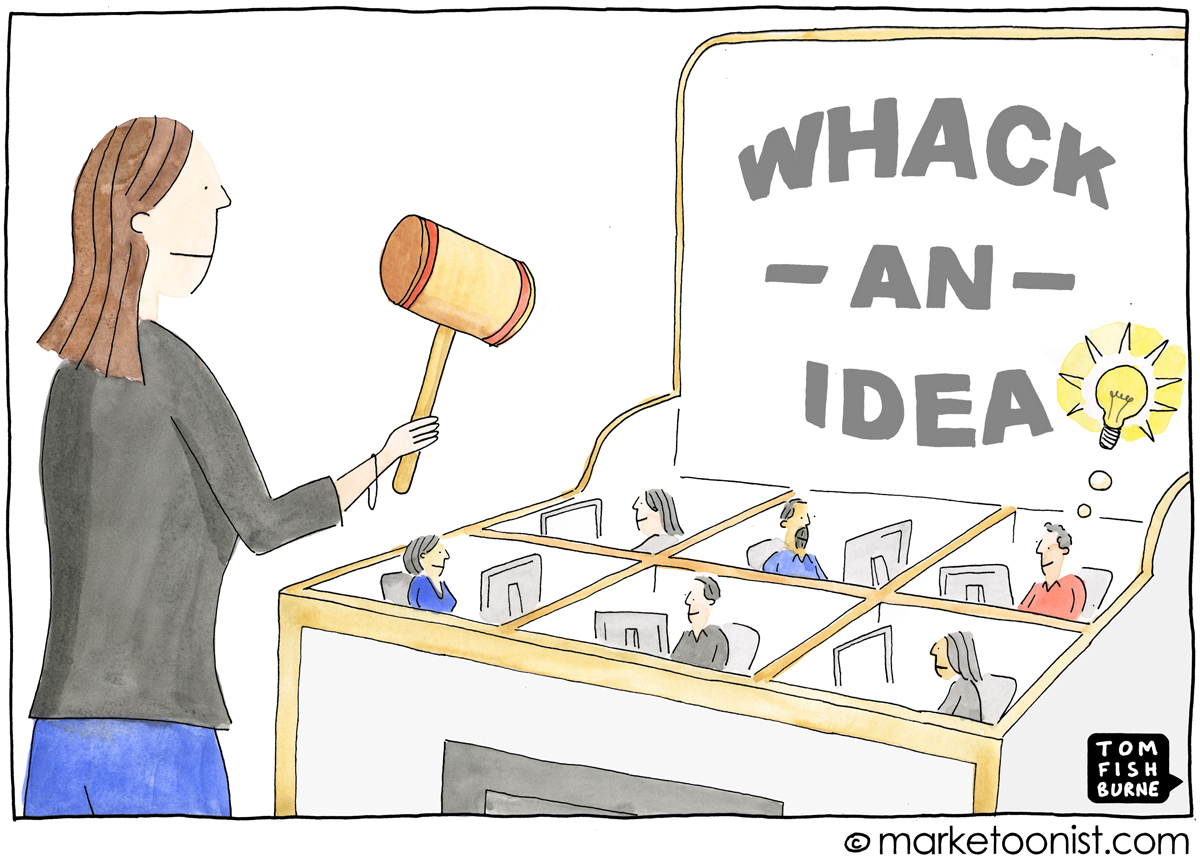

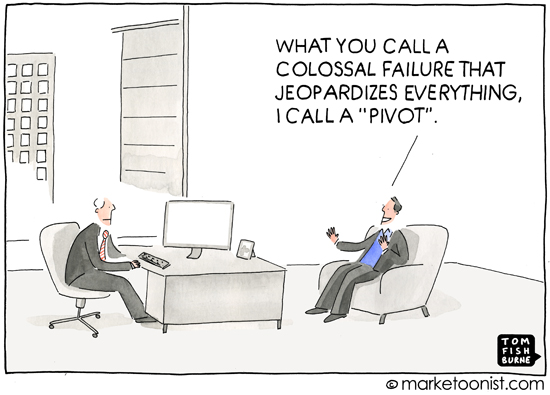

You can tell a lot about an organization by what gets punished and what gets rewarded. Stanford professor Bob Sutton famously observed twenty years ago that many organizations follow an unspoken motto to “reward success and inaction, punish failure.”

He advised instead to “reward success and failure, punish inaction.”

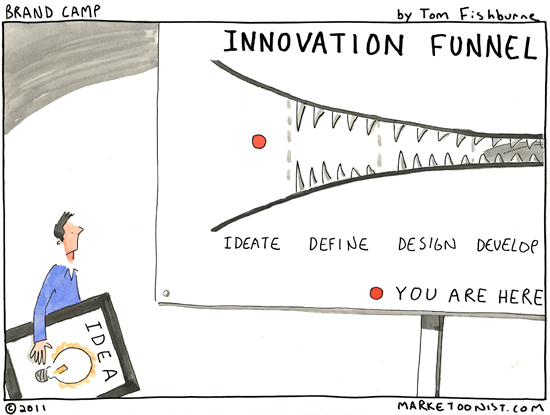

This idea of “rewarding failure” has sometimes been taken to extremes to justify an “anything goes” approach to innovation. HBS professor Gary Pisano argued that what often gets overlooked in the creative process is discipline:

“A willingness to experiment, though, does not mean working like some third-rate abstract painter who randomly throws paint at a canvas. Without discipline, almost anything can be justified as an experiment.

“Discipline-oriented cultures select experiments carefully on the basis of their potential learning value, and they design them rigorously to yield as much information as possible relative to the costs. They establish clear criteria at the outset for deciding whether to move forward with, modify, or kill an idea. And they face the facts generated by experiments. This may mean admitting that an initial hypothesis was wrong and that a project that once seemed promising must be killed or significantly redirected. Being more disciplined about killing losing projects makes it less risky to try new things.”

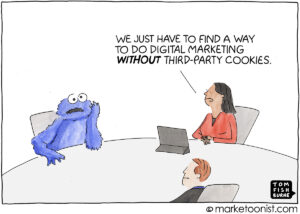

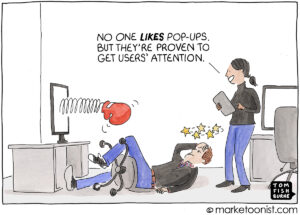

Here are a few related cartoons I’ve drawn over the years: