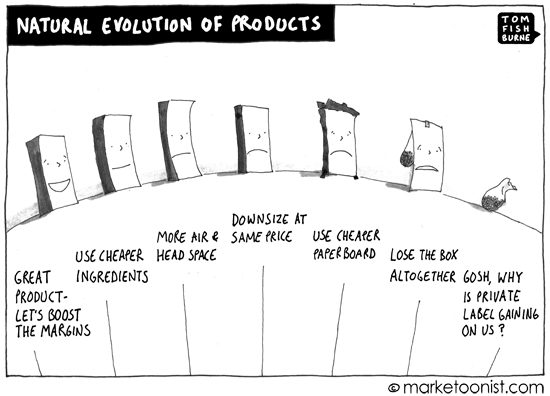

A few years ago, a yogurt brand increased its margin by putting less yogurt in every container while keeping the same retail price. So that the products wouldn’t look smaller, they kept the same packaging, which meant that every container suddenly had several inches of air at the top of the yogurt. To justify this obvious drop in value, they added a package burst that said, “Now Room For Your Favorite Mix-ins!” They tried (unsuccessfully) to make the fact that they were short-selling product into a consumer benefit.

There is constant pressure in business to improve margins through cost-cutting. This is particularly true in 2013, when consumer confidence is shaky and many community costs (particularly in food) are on the rise.

Cost-cutting can be the mother of invention, inspiring creative problem-solving and efficiency. But it can also tax product quality over time. Consumers may not notice the change in any one cost-cutting round, but the cumulative effect over time can weaken the products materially. Chronic cost-cutting was a major factor behind the horse meat scandal.

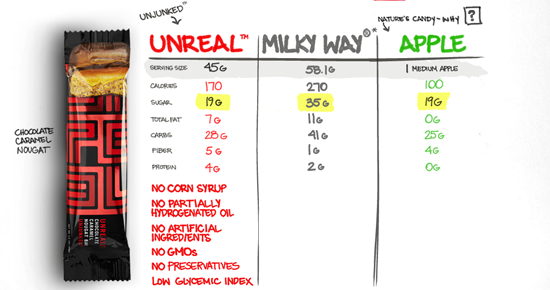

Chronic cost-cutting creates an opportunity for new brands to out-premium the premium brands. The Unreal brand launched in the US to reinvent popular food brands, starting with candy, “proving candy can be unjunked”. Their first five products are versions of Reese’s, M&Ms, Peanut M&Ms, Snickers, and Milky Way without the cheaper ingredients (corn syrup, partially hydrogenated oil, etc.).

Just as premium brands are cutting costs, private label seems to be getting better. If brands aren’t careful, the slippery slope of constant cost-cutting can lead to very little differentiation versus cheaper private label.

In the push to increase margins, it’s important to remember that there can be a cost to cost-cutting.

(Marketoonist Monday: I’m giving away a signed print of this week’s cartoon. Just share an insightful comment to this week’s post. I’ll pick one comment at 5:00 PST on Monday. Thanks!)

Here’s another cartoon I drew on chronic cost-cutting in 2007.

manas says

In the Indian context, cost-cutting by either FMCG brands or by others has most of the times implied deterioration in quality. For eg. Indian FMCG majors like Dabur and Parle have recently come up with their smaller versions of their respective beverages. Indian market understands tinkering with parameters like grammage, pricing, packaging etc. with ease. Result: Quality downgrade. Now an excellent example would be that of Minute Maid’s Pulpy Orange wherein the level of pulp content has gone down keeping everything other constant.

Tessa Stuart says

Tom, a very acute post there. We are seeing this happen in the UK food market too. Producers are squeezed by soaring raw material costs, in part because of our hard winter and very late spring, affecting farmers’ harvests. globally, changing weather patterns affect when fruit ripens, forcing innocent drinks to find other sources for their seasonal smoothie with Alphonso mangos.

The number one question I get asked about by all my food entrepreneur clients is: “Can we reduce the size, because our margins are being hammered by outside costs?”

To which, my reply is if they are start-ups, “Get that right at the beginning.” Innocent drinks, now wholly owned by Coca-Cola, have recently reduced their smoothies size. Consumers howled a bit. But that is when what differentiates the brand, high quality and a taste no-one else makes, can really ensure allegiance to it when it gets more expensive per millilitre.

Supermarket own label has really upped its game here dramatically, creating their own premium sub-ranges. Waitrose recently bought the right to use the Duchy Originals branding from Prince Charles, re-branded a ton of their ordinary lines, and voila!, the consumer pays more for the same. Waitrose also cleverly launched an Essentials range of groceries with stripped down packaging to lure Tesco shoppers into their stores and that has worked exceptionally well to bring a whole new demographic into the store who would’ve previously regarded this “posh supermarket” as too expensive.

Tom says

Wonderful comic. After several companies and working on Value Engineering projects it is a constant struggle to remember not to remove the value from the product.

BTW, I know your obliquely referenced yogurt brand. Oddly enough I noticed they had removed 2oz of product for the same price. When I called to complain, I was given the “room for mix-ins” comment as well as a comment about them “having performed market research and found out that people eat yogurt for a snack rather than meals.” (you could almost hear the phone rep wincing at having to repeat the line). But as you pointed out, the price remained unchanged. I stopped buying their brand. Fast forward a few years later and out comes Greek yogurt with its higher level of protein at the same size. Now they can charge a premium and the consumer is (surprise!) eating it in place of a meal.

Bottom line – you really can’t fool the consumer. You have to nail your product insight/consumer benefit and when you cost save or value engineer, you can’t move away from the product insight. If you do you run the risk of alienating the consumer and someone steals your market share.

Tom C says

Really interesting and incisive as always Tom.

In the Sunday Times of London yesterday, the new boss of Tesco was interviewed and completely re-enforced the point you make in your post today. I have taken the liberty of copying it below:-

Philip Clarke’s eyes were opened by the bacon. As a newish boss of Tesco, he visited the Bishop’s Stortford store to check the layout and look of a new customer complaints desk. A woman slapped some of Tesco’s Finest bacon on the counter, saying the rashers were too thin, too watery, and stuck to the pan.

A case for a refund perhaps, but Clarke wanted to play detective. He rang the bacon buyer. Tesco had cut the pork thinner to match a competitor on price, he discovered. The result was a Finest product that wasn’t fine. “We have redone our bacon range,” says Clarke, deadpan, in the supermarket’s small London office in St James’s.

It was a minor incident, but indicative of a huge hidden problem.

Clarke took over at Tesco two years ago, when the public saw it as a runaway global success story under a star chief executive, Sir Terry Leahy. The truth was grimmer. The British business, which accounts for two-thirds of sales and profits and employs 290,000 people, had been squeezed and squeezed again to fund global expansion and meet ambitious sales and profit targets. It still had a third of the market but customers, put off by unattractive stores and unfriendly staff, were fleeing to rivals such as Sainsbury’s and Waitrose or to cheaper upstarts Aldi and Lidl.

Karl Sakas says

“In the push to increase margins, it’s important to remember that there can be a cost to cost-cutting.”

Yes! To reiterate your point, Harvard Business Review recently shared the results of a 44-year study to tackle the “how do you STAY great?” question.

Researchers Michael E. Raynor and Mumtaz Ahmed found that companies that become and *stay* great (for 20+ years) do two things:

1) They don’t compete on price

3) They put revenue growth before cost cutting

Interestingly, they found many of the “success study” darlings from the past 30 years (e.g., Whole Foods) don’t make the cut after controlling for randomness and other factors. The full article requires an HBR subscription, but even without, you can see a preview with the key points here: http://hbr.org/2013/04/three-rules-for-making-a-company-truly-great/

When I consult with marketing firms, cost-cutting is important, but so is finding ways to grow revenues. Profits go up either way, but there’s a limit to cost-cutting.

Bill Carlson says

Sorry if this sounds crass but it’s our job as marketers to get consumers to pay the most we can get them to pay for what we offer and in the end, consumers set the price, not suppliers. Our free and highly-competitive market doles out rewards and punishment for pricing decisions in the form of consumer purchases and if a brand can be successful delivering less (or a lower-quality) product for the same price, more power to them.

However, that isn’t my definition of “cost-cutting…” At best, it’s the least-inspired short-cut to improving margins and it’s typically a one-time only tactic as opposed to being a sustainable long-term strategy for growth. Hopefully the short-term margin “windfall” of such actions is being channeled into true cost-reduction or even better, some new product development activities.

The change by Coke (and I assume others) from a “case” being 24 cans down to 20 was almost not noticeable but the motivation was instantly apparent. Not sure how that has worked out for them and their retailer-partners but I admit it, I’m still buying Coke, so they win this round.

But they’ll have a tough time cutting that back to 16 and charging the same or similar prices. Well, I say that now, but…?

(And after reading the yogurt comment, I should probably check to make sure those are still 12 oz. cans and not 11!!! 🙂

Jen Nelson says

Thanks for the chuckle out loud, like most good comedy, it made me laugh because it hits so close to home.

Sadly, I have worked on one brand that (by the time I got there) couldn’t “afford the cost of goods (COGs)” (according to finance/management) to bring the product up to meet even Private Labels performance and features. But that wasn’t always the case, in fact it was once the market leader, and one of the original category creators – but you can easily imagine what is happening to this 100 year old brand now. It’s hard to imagine that if that company doesn’t accept the costs of being competitive with the modern market — or at least competitive with Private Label soon, it simply won’t continue to exist in the market at all.

So what is the greater NPV? Higher COGs and less profit for another 100 years +, or more profit for the next 1 to 5 years before all retailers stop carrying you for the slow turn rate? It doesn’t take a very complex spreadsheet to imagine the answer. Sadly, internal optics and political dynamics often get in the way of good decision making and will to change.

If you make a great cartoon on that though, Tom – it might be TOO close to home and I’ll shed a tear instead of a chuckle.

Teresa Olding says

I want to say thank you to all those who share their rich experiences in the comments after great tee up by Tom’s cartoon and article.

I recently forwarded a Monday newsletter to a recent college grad with the recommendation to immerse herself in all the content of this site after she complained about an internship that resulted in hours of monotonous and empty Facebook posts and a fear of a repeat experience in the future.

John Bowman says

Hey, Tom, I got a big (if painful) chuckle from this cartoon, as I’m sure you did when creating it.

When Gordon Bethune became CEO of Continental Airlines, he flew it on an upward trajectory from worst to first with business flyers. Explaining what he intended to do to achieve that success, Gordon would say: “You can make a pizza so cheap, no one would want to eat it, much less buy it.”

Prior to his leadership, that airline was managed (as most are) as a high-volume/cost-cutting operation. (Hence, the inedible pizza analogy). He opposed that self-defeating approach. Instead he put high-value customers first (“from backpacks to briefcases” was his memorable soundbite.) Then he aligned all operations to deliver a consistently superior experience for high-value customers. He knew margin-improvement would surge from high-value fans, not by cost-cutting.

Concetta says

Wow, Tom. I see you bought into Unreal’s marketing spiel.

Ingredients to a Snickers bar: MILK CHOCOLATE (SUGAR, COCOA BUTTER, CHOCOLATE, SKIM MILK, LACTOSE, MILKFAT, SOY LECITHIN, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR), PEANUTS, CORN SYRUP, SUGAR, MILKFAT, SKIM MILK, PARTIALLY HYDROGENATED SOYBEAN OIL, LACTOSE, SALT, EGG WHITES, CHOCOLATE, ARTIFICIAL FLAVOR. MAY CONTAIN ALMONDS

Ingredients to an Unreal 8: MILK CHOCOLATE (CANE SUGAR, CHOCOLATE, COCOA BUTTER, MILK POWDER, ORGANIC BLUE AGAVE INULIN, SKIM MILK, SOY LECITHIN, VANILLA EXTRACT), CARAMEL (TAPIOCA SYRUP, CANE SUGAR, FRUCTAN (PREBIOTIC FIBER), ORGANIC PALM KERNEL OIL, WHEY, MILK PROTEIN CONCENTRATE, ORGANIC CREAM, VANILLA EXTRACT, SALT, SOY LECITHIN), PEANUTS, TAPIOCA SYRUP, CANE SUGAR, ORGANIC PALM KERNEL OIL, SKIM MILK, PEANUT FLOUR, SALT, HYDROLYZED MILK PROTEIN, EVAPORATED CANE SYRUP, SOY LECITHIN CONTAINS PEANUTS, MILK, SOY. MAY CONTAIN TREE NUTS, WHEAT.”

I can eat a Snickers bar as someone with a gluten allergy. I can’t eat an Unreal bar. Why? Because they claim they’re organic and healthier, yet they use more substitutes than the unhealthy candy. And Palm Kernel Oil is 80% saturated fats, not so unlike the partially hydrogenated oil that the Snickers company uses.

The rest of your points, however, are very valid. I used to eat a lot of packaged meals that would say they now came with “more sauce!” when what they really meant was that they decreased the noodles or rice to add more liquid of some sort. It was completely transparent and I stopped buying them. The consumer can see through this stuff and they can share their thoughts with the world on it – another win for social media.

Insider says

In our company, we have a fancy name of cost-cutting: Design To Value or DTV attempts to put a shine on what is just another shameless cost-cutting exercise. We paid the world’s largest management consultancy big bucks to peddle us one of their off-the-shelf products.

When the project was being run, teams were asked to detail every potential cost svaer, even the unrealistic ones. This was presented to the C-suite who were delighted at the big numbers. Now, we’re expected to deliver every single hypothetical cost saving under the guise of “consumers and customers only need what they need” Let’s not give them the highest quality products.

Rose says

In reference to the Unreal products – I have a problem when the marketing offers a comparison that isn’t real. The weight of the unreal bar above is 45g, the weight of the Milky Way in the comparison is 58g. Yes, the nutrients are still more positive whether the bars are compared on an even weight basis or not, but it troubles me when companies trying to be ‘better’ than the other guys go about it in a sneaky way. Also agree with Concetta’s comment above.

The cartoon and article this week hit very close to home for me as well – I am a product developer, but work with the teams in charge of cost cutting as well. Nothing is more dissapointing than making a great product, only to have it stripped down after launch.

Not all cost saving work has a negative impact to products or consumers, I led a cost savings project in the past that was also a product improvement; but from my vantage point those types of projects are few and far between.

tomfishburne says

Great commentary from so many perspectives on this one! Teresa, thanks for highlighting the value of the comments that readers generously share in these posts, and I’m glad that it struck a chord for the recent college grad you contacted.

Thanks also to Concetta and Rose for highlighting the flaws in Unreal’s marketing approach. I’m not that close to how their brand delivers, but I am fascinating by their positioning.

This week’s print goes to Tom C. I really like the story of Tesco’s “Finest” bacon that was no longer “fine”. Having once been a supplier to Tesco, I’m very familiar with that squeeze.

Thanks!

Rob Mortimer says

Spot on.

You should also check out the Grown up chocolate company for similar high quality versions of typical snacks. (http://www.thegrownupchocolatecompany.co.uk/)

I think this Calvin and Hobbes cartoon also sums up what is going on here…

http://pecuniarities.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/01/calvineconomics.jpg