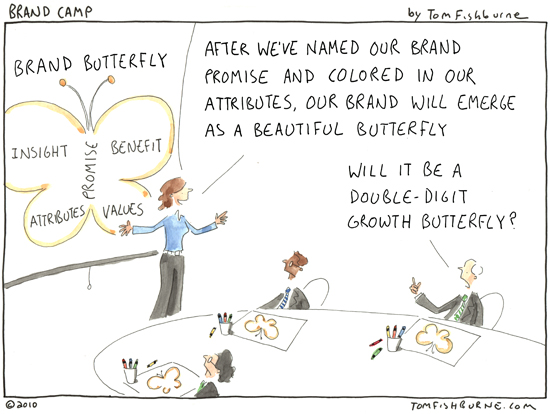

Every brand has some form of a brand butterfly, whether they call it a brand onion, a brand architecture, a brand key, a brand pyramid, a brand d.n.a, or a brand unicorn. It’s the one-page blueprint of the brand.

When written well, it can be an invaluable resource. It sparks new ideas and helps guide all of your decisions on whether an idea is “on brand”. When I first learned about brand architectures at General Mills, we talked through the Cheerios brand architecture as an example. Cheerios stands for “nurturing” at its essence, which extends from the toddler first finger food moment to its cholesterol-lowering whole grain. So, a free children’s book tucked in the cereal box would be on brand, but a $10 Dominoes pizza coupon would not.

Yet many brand architectures are full of insider marketing lingo that make them seem ridiculous to everyone else. A brand architecture is most valuable when its easily understood by everyone on the extended brand team. My friend Matthew said that they should pass the “IT guy test”, meaning that the IT guy should be able to understand the brand from reading it.

Too often, brand architectures are written by group committee, which makes them blandly acceptable to everyone but not that inspiring to anyone in particular. Defining a brand promise in a group reminds me of that classic charades scene in “When Harry Met Sally”. They’re all shouting guesses to the charades answer and Jess suddenly blurts out, “baby fish mouth … baby fish mouth”. Everyone stares at him because his guess is complete nonsense, but it sounds right to him because he’s so close to it.

I thought of “baby fish mouth” years ago when we finally settled on “Healthy Haven” as a brand promise for Green Giant. It doesn’t really mean anything without a lengthy explanation but it was the only option everyone could agree on.

There’s diminishing returns the more time you spend on a brand architecture. Time spent debating a brand architecture is time not spent developing ideas based on it. Rather than chase perfection, it’s better to run with an earlier imperfect draft and get ideas into the market to test what resonates.

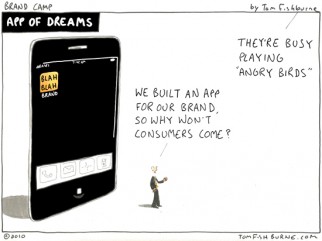

I came across this great post last week from WordPress founder Matt Mullenweg:

“Usage is like oxygen for ideas. You can never fully anticipate how an audience is going to react to something you’ve created until it’s out there. That means every moment you’re working on something without it being in the public it‘s actually dying, deprived of the oxygen of the real world … By shipping early and often you have the unique competitive advantage of hearing from real people what they think of your work, which in best case helps you anticipate market direction, and in worst case gives you a few people rooting for you that you can email when your team pivots to a new idea. Nothing can recreate the crucible of real usage.”

Matt writes form the vantage point of software development, but the idea is just as applicable for consumer products. Physical products may be less flexible, but brands can quickly experiment with promotion ideas, communication experiments, and marketing tests. You’ll learn infinitely more from seeing how your ideas are received in market than pontificating your brand promise.

Spend less time word smithing and more time experience smithing.

@euonymous / Mary Cole says

Amen. Being guilty of overthinking things from time to time, myself, I agree there is tremendous value in getting it done, getting it out there, and modifying as necessary. Overthinking just slows you down. It is important to know when one’s personal tendencies work for you and when they work against you so you can plan accordingly. Nice reminder!

Jackie Huba says

Tom,

Love this!! And so relevant. Was just sitting in qualitative research sessions for a client last week whose output will help them build their brand key. The brand has been in the marketplace for 5 years already. It seems challenging to try to map the brand key for what customers ALREADY think the brand is about vs. launching a new brand with a architected brand key. Thoughts?

tomfishburne says

Great question, Jackie! I think that building a brand key for an existing brand is challenging because less is up for grabs, but in some ways it’s easier because you have actual consumer feedback to tell you what your brand means, rather than basing it on the navel gazing of the team. The big trick is being deliberately exclusive and choosing one consumer profile to gear the brand toward, rather than designing it for everyone. The temptation is to make a brand broadly appealing to everyone, but a brand key is most valuable when it’s tightly targeted to the smaller, most loyal group. Design for the few and a broader group will follow. Design for everyone and risk being not that meaningful to anyone in particular…

Dennis Van Staalduinen says

Awesome as always Tom! I particularly appreciated the phrase “brand unicorn” which got me riffing a bit on http://www.begtodiffer.com – with props to you of course.

Thanks!

Oliver Holtaway says

I’m in the middle of a “master narrative”-type project right now where we are recasting our client’s long-gestated but somewhat marketing-speak brand architecture into plain, engaging English that tells a story rather than just listing positive attributes and past track record. They’re a great client and are committed to the project, but it’s been eye-opening to see how much internal resistance crops up over little phrases and ideas that seem fairly innocuous to me. On the plus side, I’m learning a lot about their business sensitivities, but I’m seeing how challenging it is to fight against the institutional bias towards blandness – this post is inspiring me to fight my corner!