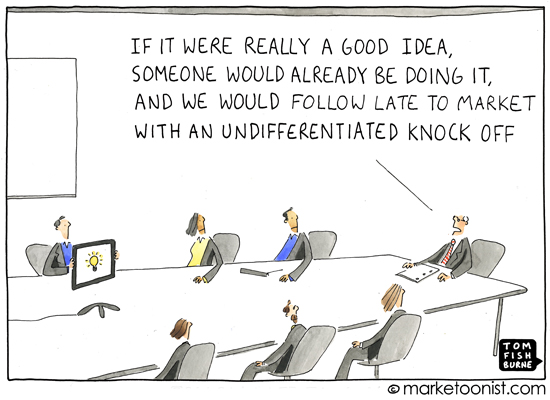

One of my favorite idea killers is the statement, “if it were really a good idea, someone would already be doing it.”

In innovation, we often fixate too much on the competition. We benchmark and validate ideas based what everyone else is doing. This cycle of one-upmanship makes it hard to launch something truly new and different. It also creates a lot of me-toos.

My friend Sasha pointed me to “The Creative Monopoly“, a David Brooks piece on PayPal founder Peter Thiel’s business philosophy.

“Instead of being slightly better than everybody else in a crowded and established field, it’s often more valuable to create a new market and totally dominate it. The profit margins are much bigger, and the value to society is often bigger, too … He’s talking about doing something so creative that you establish a distinct market, niche and identity. You’ve established a creative monopoly and everybody has to come to you if they want that service, at least for a time”.

Of course there’s a role for the fast follower in innovation. But when everyone is a fast follower, who is there to lead?

I once heard innovation writer Doug Hall say, “If you’re not meaningfully unique, then you’d better be cheap.”

(Marketoonist Monday: I’m giving away a signed print of this week’s cartoon. Just share an insightful comment to this week’s post. I’ll pick one comment by 5:00 PST on Monday. Thanks!)

Timo Jappinen says

How to true, Tom.

But I’m afraid your cartoon is slightly optimistic. Why? Because it assumes that eventually they will act.

Bill Stiles says

Thanks, Tom. A great week-starter this morning.

I find too often the voice that thwarts a good idea is not a suit at the end of the table, but one from my own head that whispers all the reasons something can’t, shouldn’t or won’t get done. The power of that inner voice for ill or good is a factor in every market equation.

Let’s admit that sometimes the critical voice is right, whether its in the first or third person. A few years ago a man in a tie told me an idea of mine was past its prime. I did not listen and it cost me $120,000.

The cost of that inner voice, however, has much more impact on the bottom line. If we could develop an app to tell our cerebral cortex when to pull back and when to push like crazy, that could be a good idea.

Thanks.

Bill Hudgins says

You know this commentary was very insightful . . . We recently setup with Hubspot as a part of our efforts to more effectively convey who we are and what we do to the marketplace. I am having difficulty determining how to convey and leverage what I consider to be our greatest strength . . . . our collective intellectual capital and varied industry expertise. We are a very eclectic group and I would like to think that we could package and present the value that we bring to the acquisition of a host of products and services . . . (that in some respects are rather banal) . . . as a formidable differentiator in the marketplace. When someone needs a particular product or service in a genre that they are quite unfamiliar with it is contingent on someone like us to put them at ease and take the mystery and hassle out of the process. So I think our message needs to evoke confidence and assurance that we are the group to employ as a part of that process . . . kind of like Greyhound’s marketing slogan “Leave the Driving to Us!”

Bill Carlson says

It’s certainly wonderful to be in that all-too-rare position of creating a new market and dominating it, but even then, market domination is a transient thing. Eventually someone will find a way to compete and you come back to this issue.

The old saw “success is a journey, not a destination” clearly has its roots in reality. And one CEO I worked for tweaked this a little by replacing “success” with “leadership”, which I think is even more compelling.

Anyway, successfully competing requires a range of ONGOING activities in parallel — looking for innovative new products to offer, leveraging the products you have, and thinking ahead to when the former becomes the latter.

We don’t do enough of that thinking ahead stuff. I advocate “war games” where a brand creates two teams — one which works on how to step past their competitors and the other working on how they would step past themselves if THEY were the competitors. Considering how the competition might respond to new market challenges can spur ideas about to how to counter those moves. Etc.

That being said, the business climate these days is a little skewed toward the conservative with brands AND people at least as concerned (maybe more?) about protecting their current position versus taking risks. Successful companies will shift back to again being open to new ideas and recognizing that the term risk-reward has two words in it, not just one…

Tim says

Sometimes I wish the markets would be even more harsh on second-rate companies. It’s amazing that, given the levels of competition in most industries, that inferior brands stay afloat. For example, in Western New York we have two major grocery chains: Wegman’s and Tops. Wegman’s is customer focused, wins awards every year for best place to work, and provides great value at great prices (not mention that shopping there is a pleasure). Tops is typically more expensive for less thrilling products, offers nothing unique or innovative, and has little “customer experience” focus. Very generic grocery store.

After many years in business, why doesn’t Tops go bust? Perhaps location and momentum will keep them alive in the short term, but Wegman’s (the innovative brand) is the one expanding robustly outside the Western New York region. The takeaway for me is that innovation and customer focus will pay off after many years, but many companies won’t make that type of investment, being too focused on optimizing short-term earnings.

DSprogis says

Tom,

Great piece! … and the mentality of the suit at the end of the table opens the door for start-ups; the guy with the idea leaves and implements the idea himself. So in many ways, I love that guy in the suit that says “no” because he creates external opportunities.

I have to take some exception, however, with Thiel’s business philosophy. There is very little protecting the “creative monopoly”, the entrepreneur has very limited time to build and dominate. Entrepreneurs may not like VCs, but they are a necessary evil in building the idea, the organization and the credibility fast.

Keith says

Uh oh. Samsung’s entire global policy on product just got shot down in flames.

What does this say for innovation? And what does it mean when the marginal benefit of most goods/items/markets is decreasing over time? I think that’s probably the key insight to Peter Thiel’s statement. By being a fast follower or a late follower you’re entering a market where the marginal benefit of a slightly improved product is ever shrinking. By opening a new market (no easy feat in itself) you are capturing the lions share of the value.

A nice example may be the chap who decided to start making Neuticles… http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2012-04-25/odd-jobs-prosthetic-dog-testicle-maker

Keith says

Can I also just add that your post pretty much sums up Peter Thiel’s view on the whole “0 to 1” vs “1 to n” concept as outlined in this worthwhile read http://blakemasters.tumblr.com/post/20400301508/cs183class1

Steve Chayer says

Tom,I read a lot and I read a lot of thoughtful and educational blogs. I read all of yours and this one by far and away has been the most impacting. Your cartoon and commentary lead to the David Brooks summary of Blake Masters’s classroom notes on a Peter Thiel lecture and then thoughtful, insightful comments from fellow readers. All of this I read voraciously and passed on to friends and associates. I learned a lot. Thank you!

Jeff Lash says

The funny thing is that most often there *is* someone else doing it. Amazon wasn’t the first online bookstore. The iPod wasn’t the first MP3 player. The Jeep Wrangler wasn’t the first off-road vehicle. Successful companies don’t use “if it were really a good idea, someone would already be doing it” as an excuse for not moving forward, just like they don’t use “because no one else is doing it, it must be a good idea” as a rationale for moving forward.

Often the most successful “innovations” aren’t 100% new to the world, they are just different on criteria which matter to customers to make them truly innovative.

Allen Roberts says

There have been libraries written about differentiation strategy, full of long, meaningful technical terms and cliches, mixed in with some good thinking, all distilled into a simple drawing.

Whoever said “a picture tells a thousand words” was thinking of this cartoon.

Great work Tom.

tomfishburne says

Hi all,

Great commentary everyone, thanks! This weeks print goes to Bill Stiles for the reminder that often the critical voice comes from inside, not from a gatekeeper. The inner voice is often the harshest critic, and what we have to overcome to pursue annoying particularly innovative. It’s true too that sometimes the critical voice can be right. The trick is in acknowledging that without squashing any idea that seems too risky.

Thanks,

-Tom

Sue says

If you had a “like” button, Tom, I’d like your comment/Bill’s and also Jeff Lash’s …

But I’d add something Beverly Cleary said she learned from a philosophy professor that haunted her her entire writing life, something like this: great ideas are floating around in the universe, if you spot one, grab onto it quickly…because if you don’t grab it and establish it as your own, you can bet someone else will.” The Internet has made the reality of this even more apparent. But that’s why I like Jeff Lash’s observation. The HOW you do something is even more important than the WHAT.