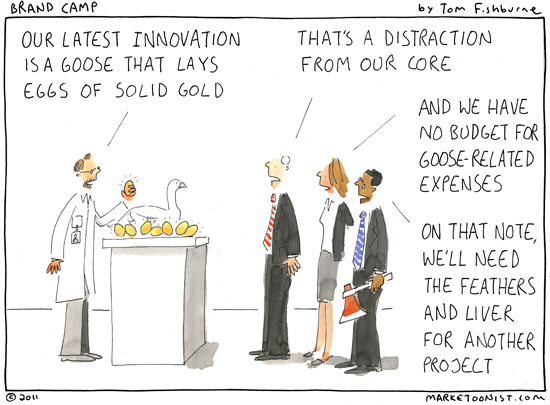

There is an inevitable friction in bringing ideas to life within a company. That friction can polish an idea and make it stronger, sand the edges of the idea and make it weaker, or kill the idea altogether. Anyone who works in innovation is familiar with that tension. Navigating it is part of what makes innovation so difficult.

Malcolm Gladwell wrote an illustrative New Yorker article on the mythic 1979 story of Steve Jobs and Xerox PARC. After negotiating with Xerox, Steve first saw a demo of a mouse-enabled user interface at Xerox PARC, which inspired the development of the Macintosh.

Xerox has been widely critiqued for not recognizing the full potential of the personal computer and for letting this idea pass by. Gladwell profiles one Xerox engineer in particular, Gary Starkweather, who epitomized the tireless innovator trying to bring ideas to life within large companies. Starkweather summarizes his career frustration as, “it was like me saying I’ve discovered a gold mine and you saying we can’t afford a shovel”.

Yet Gladwell also profiles the other side of the story. Even though Xerox was not well placed to commercialize a personal computer, that bleeding edge research led to the invention of laser printing, which fit the Xerox business model and was a booming success.

“The interests of the innovator aren’t perfectly aligned with the interests of the corporation. Starkweather saw ideas on their own merits. Xerox was a multinational corporation, with shareholders, a huge sales force, and a vast customer base, and it needed to consider every new idea within the context of what it already had … It was ever thus. The innovator says go. The company says stop — and maybe the only lesson of the legend of Xerox PARC is that what happened there happens, in one way or another, everywhere.”

The modern day Xerox PARC replied to Gladwell’s article with a fascinating post on the merits of open innovation as one way to resolve that friction. They make a distinction between “invention” as the manifestation of an idea and “innovation” as an idea that reaches the market and impacts people’s lives.

“If Steve Jobs came to PARC today, there would be a much better understanding of his goals, our goals, and what we would want to accomplish – together – through open innovation. Because that’s what’s different: open innovation provides a framework for these conversations and interactions. Through the pioneering work of Henry Chesbrough and others, there is now widespread awareness and practice of Open Innovation as a means for companies to leverage inventions and innovations from external parties. This can range from simply licensing IP (from or to others) and relying on outside organizations to help you see what’s possible, to co-developing and leveraging someone else’s investment to be tailored to your needs.”

There is no longer merely a “go” or a “stop” in innovation, as Gladwell originally characterized. There are other options for the golden eggs.

Kevin McFarthing says

Nice article, Tom. Given the future timeframe a lot of groups like PARC take, one thing they struggle with is exploring areas that aren’t aligned with today’s strategy but which they believe can form the strategy of the future. This means they are doing more gambling than planning. Nothing wrong with this as such, as long as somebody very senior (CEO or direct report) has the overview, and manages the bets like an investment portfolio. They need to be careful to avoid the personal interests of the research director,

Kevin

Priz says

Could I also recommend Malcolm Gladwell’s book “Outliers” as a thought provoking work on the combinations of hard work, history, ‘luck’ and success.

Tom Denford IDCOMMS says

This is a great one Tom. From the agency side this is much like talking to brands about their social media strategy, they like the idea of what it might offer but they are not organised internally to be able to actually do it. Social media is a commitment much like building a department of the company (eg a customer service department) rather than a short lived campaign launch. Yet because the marketing department is often not organised (rewarded) to be able to do this, it gets broken into its constituent parts or diluted in order to fit their current marketing model.

That said, we firmly believe that it takes more than vision or bravado to adopt such an approach, too many marketing departments are still structured badly, reflecting the old (siloed) broadcast model of communications and therefore not ready to do social media properly. For many brands they need to go through a period of re organisation and house-keeping internally before they can really commit to working in a new way with external agencies.

Hutch Carpenter says

One of the better frameworks I’ve seen for describing the realm of corporate innovation is from a couple researchers, Ysanne Carlisle and Elizabeth McMillan. The think in terms of a spectrum of control around innovation:

> Totally random and without pattern

> Chaotic

> Complex

> Hierarchical

> Mechanistic

In terms of making innovation a reality, the two ends of the spectrum are not helpful. “Totally random” is a popular notion of innovation (“it just happens”), but one that isn’t true and offers little guidance. “Mechanistic” is as bad as it sounds. Overly controlling everything. The Gary Starkweathers would never get anywhere in such an environment.

It’s that center part, “Complex”, and its edges with its two neighbors “Chaotic” and “Hierarchical”, where innovation gets done. Here’s why…

The researchers see innovation as essentially one of two types: exploitation or exploration.

Exploitation: Incremental innovations generated off existing knowledge, competencies and capabilities. Short-term view as how to maximize current knowledge assets.

Exploration: Discontinuous innovations tapping new knowledge and competencies the organization doesn’t currently possess. Requires a long-term strategic view.

Companies in exploitation mode will tend toward the border between Complex and Hierarchical. They focus on extending existing knowledge and operations. As you note, it was a great fit with their existing business model.

Companies in exploration mode need to verge between Complex and Chaotic. Their job is to stir things up and tap new knowledge. Too much control is essentially sanding the idea down to nothing.

So when do companies operate in exploitation mode versus exploration mode? Generally speaking, when external environments are more stable, they will follow an exploitation path toward innovation. That makes sense, because things are going well. And firms only have but so many resources, so they tend to be put in to what’s working for a company. When external environments are unstable, exploration becomes more prevalent. A natural response to the need to change operating models before the company falters. Although sometimes that response is delayed for too long.

Think about Xerox’s environment back in the day. Exploitation of knowledge for their existing business model made a lot of sense. The company bordered on hierarchical in its innovation culture. Yes, in that environment, the PC was just a non-starter. Not because of the stupidity of those working there. But because the company was operating in a relatively stable environment.

I explore (uh…pun?) this more fully in this blog post, “Innovation Thrives between the Lines of Chaos and Control”:

http://www.spigit.com/2011/02/innovation-thrives-between-the-lines-of-chaos-and-control/

Hutch Carpenter

VP of Product

Spigit, Inc.

PARC Online says

Love the cartoon, Tom! Thank you, too, for your take on the innovation discussion between the New Yorker and PARC blog.

@Kevin — Regarding managing innovation bets like an investment portfolio, do check out (and share your comments!) on our post on portfolio management: http://bit.ly/parcpm

@Hutch — Will check out your post. You would find the post on portfolio management interesting as well, especially the notions of “harvesting” and “investment” modes: http://bit.ly/parcpm

tomfishburne says

Wow, great comments. Thanks, everyone, I learned a great deal this week. This week’s winner is Hutch Carpenter. That’s a wonderful framework that you shared, and I also enjoyed your blog post. Many thanks. A signed cartoon is on the way!

Kevin McFarthing @InnovationFixer says

Hi Lawrence (PARC Online) – I really liked your post on managing the technology portfolio. I would expand it further. The portfolio approach you outline includes the technology programs excluding exploratory research. It also (presumably) excludes other R&D programs within Xerox. Is the portfolio viewed as a whole within Xerox? It will be essential to have similar risk/return data to do this, but in my view it is essential for every company to take a view on its total R&D investment, and judge whether it is appropriately balanced for its long term goal, its need for growth and its appetite for risk.

Kevin McFarthing

Innovation Fixer Ltd

PARC online says

Hi Kevin, Thanks for your response (and for taking the time to read that post on managing research as a portfolio: http://bit.ly/parcpm)! We responded to the comment you left on that post…

Tom, thanks for sparking – and hosting – this discussion.

European Inventor Award says

This is really spot-on. We’ve been discussing the barriers to innovation a lot in the past month, and found out just how difficult it can be to develop an idea no matter how good it is. You can check out our Facebook page for some of the examples we’ve found. http://www.facebook.com/europeaninventoraward

fustian says

While the mouse itself was invented at Xerox, people at Apple that were up on the lastest IT research were already trying to sell Jobs on a bitmapped user interface. They took him to Xerox so he could see a working version of one.

Peter says

Thanks for the free license for blog posts. I have just posted this cartoon on my blog at theleadershiplamplight.com

Great work Tom!