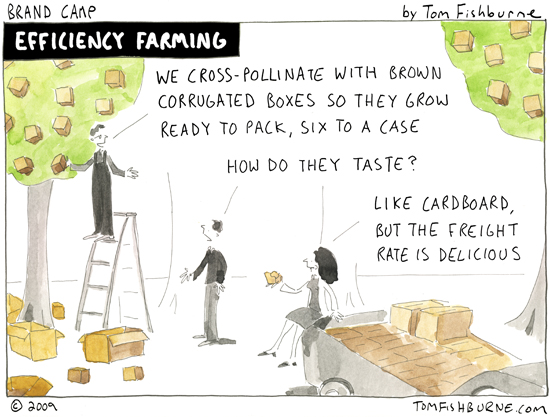

There’s constant pressure in business to make things as efficient as possible. In every project, the fat is trimmed, the edges are sanded, and the processes are streamlined. It’s how you bring scale to ideas. It’s how you improve margins over time. But far too often, the uniqueness of an idea gets lost in all the efficiency.

I was reminded of this recently when evaluating a couple different bottle designs. One was incredibly unique and differentiated, but inefficient all the way through the supply chain to the retail shelf. Another was über-efficient, but, not surprisingly, too close to the rest of the category.

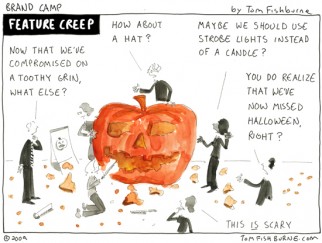

In the end, we kept at it until we found a middle road that pushed the boundaries without being too disruptive. It was the type of collaborative compromise that’s part of innovation in the trenches. But compromise can sometimes be a wet blanket to good ideas. The hard part is compromising without sacrificing. How do you make an idea stronger, not weaker, by the diversity of thought that went into it?

Walking down the grocery aisle sometimes reminds me of the “Little Boxes” theme song from Weeds:

“There’s a green one and a pink one

And a blue one and a yellow one,

And they’re all made out of ticky tacky

And they all look just the same”

Design has many masters. Efficiency is constricting one. How disruptive can you be when you’re innovating in a very small box?

Think about how much design thinking is put into the last 5-seconds at shelf, as opposed to the whole lifecycle when you’re actually using the product. Shapes are chosen for efficiency on shelf (not taller than the shelf height, not too wide to take up two facings, not too deep that you can’t fit enough on shelf). Because the shapes end up so similar, the graphics overcompensate by shouting “Buy me!” Design decisions are often made by eye-tracking tests.

Yet, when you get the product home, do you really want it shouting at you? Do you really want it to be a little box made out of ticky tacky that all looks just the same?

Last year, I toured the ginormous warehouse of Ocado, the leading web grocer in the UK (think Webvan, but their business model works). Because of this warehouse model, shoppers only discover and shop brands through a web interface, never a retail shelf. So, the last 5-seconds at shelf constraint simply doesn’t exist.

Down the road, when more and more shopping is done this way rather than the retail shelf, what impact will this have on product design?

Instead of farming for efficiency, it could allow us to farm for what is most remarkable.

Paul Williams says

Tom,

I have found – when brainstorming – efficiency is what can prevent remarkable ideas being discovered.

Our nature seems to lean toward that trimming, sanding, and streamlining you mention.

We do that with our thoughts and ideas when brainstorming. We automatically trim out what we think won’t work, sand the crazy idea to something smooth, and streamline the “we’ve tried that before” ideas. Why bother calling these out – they’re a waste of time… not efficient to add to the idea list.

With each participant in a brainstorm or strategy session self-editing like this – so many potential ideas never see the light.

Long story short, similar to the product production process you’re talking about… the idea production process needs to be less “efficient” so not all the ideas end up coming out the same.

Beth S. Miller, ABC says

Tom,

I’m always amazed at how well you capture the sheer lunacy of some branding efforts. Farming efficiency reminds me of my work in the late 80’s and ’90’s with a couple of tech firms.

We got caught in cycles of analysis paralysis. Over thinking each detail of a new product to the extent that by the time we launched, our real window of opportunity had closed. Worse, the product was often so dumbed down, or had had the creativity wrung out that it had zero appeal.

I sometimes feel like you’re in my head with your insights. I love my mornings at Brand Camp.

Ted L. Simon says

Tom,

Once again you have accomplished in one small panel what so many cannot capture in a thousand powerpoint slides.

Bottom line, there’s a point where efficiency becomes INefficiency, as in preventing the development of a distinctive brand that attracts customers and builds long-term loyalty. You can’t put THAT in a cardboard box!

Ted

@tedlsimon

Tom Fishburne says

Really appreciate the great comments, Paul, Beth, and Ted…

Rich shared this link that shows that truth is stranger than fiction: http://ow.ly/Bd4Q