Faris Yakob wrote an interesting piece last year on what motivates consumers to buy, particularly in the few seconds a consumer spends at shelf. He wrote:

“In 2005 P&G coined the term “first moment of truth” to describe the importance of packaging in their marketing model. The first point of contact is encountering an advertisement, the second is when they take an action towards the brand such as visiting a store or searching the web, the third is when they find it.

“Then all prior brand communication comes to bear on a single moment: the three to five seconds when the consumer stands in front of the shelf and decides what to buy.

“Interesting and innovative packaging can make up for lower media weights, as with craft beers or companies like Method soap that focused on making their bottle something people would be proud to display in their homes.”

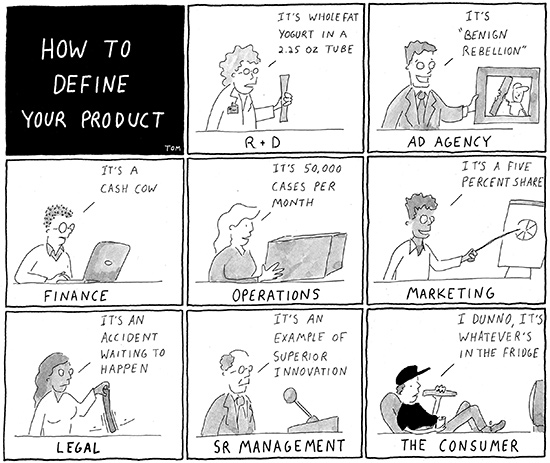

A few years before I worked on the Method soap brand Faris writes about, I was a Marketing Intern at General Mills. The CMO at the time, Mark Addicks, shared some marketing career advice that always stuck with me. He warned that too much time in the marketing offices would lead to breathing our own exhaust.

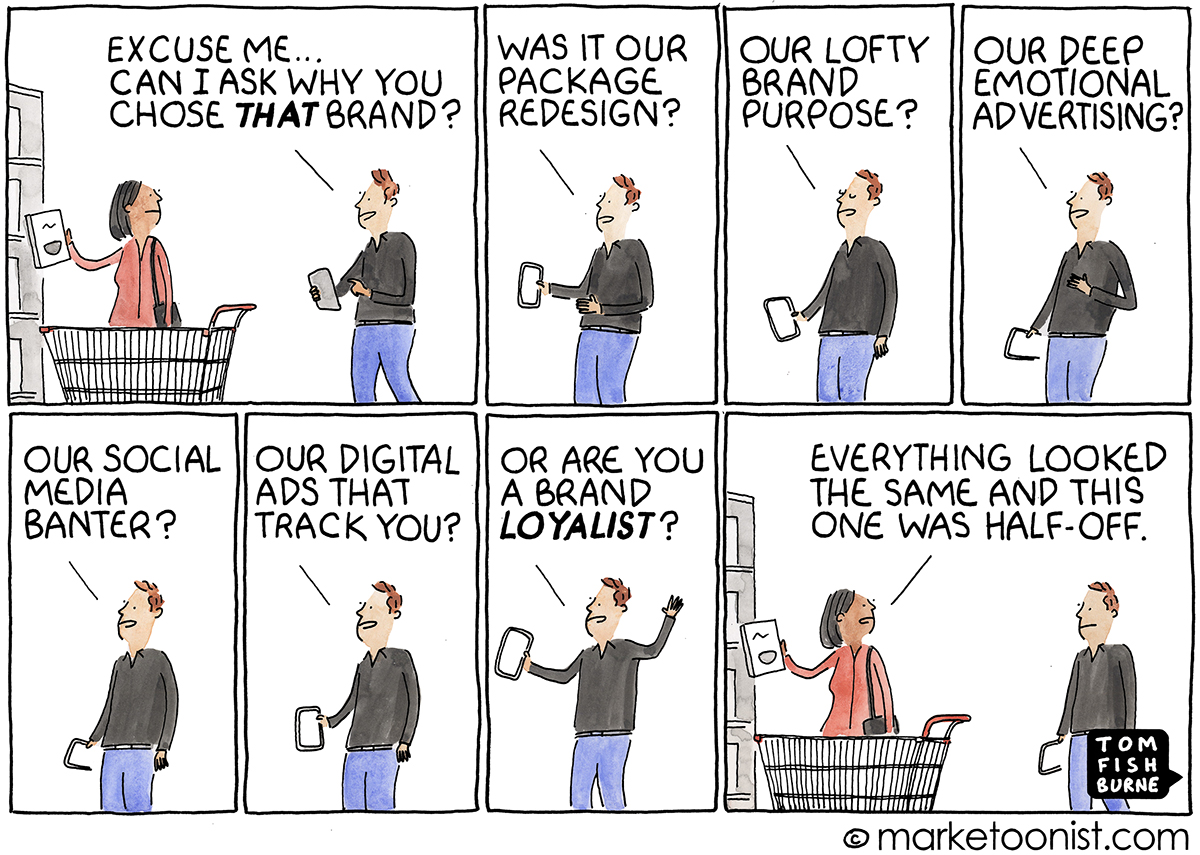

In particular, he urged us to spend as much time as possible in grocery store aisles, silently watching as people shop the categories we work on. He said we’d soon discover that many of the things that marketers obsess over don’t have nearly as much impact as we think in the actual moment someone choses to buy.

Mark went on to suggest that whenever we join a new brand team, the first thing we should do is take out an empty notebook and fill if with everything we think we know about the brand before we start working on the brand. That notebook will then become a valuable resource, he said, because it’s uncorrupted with the institutional knowledge big companies have access to.

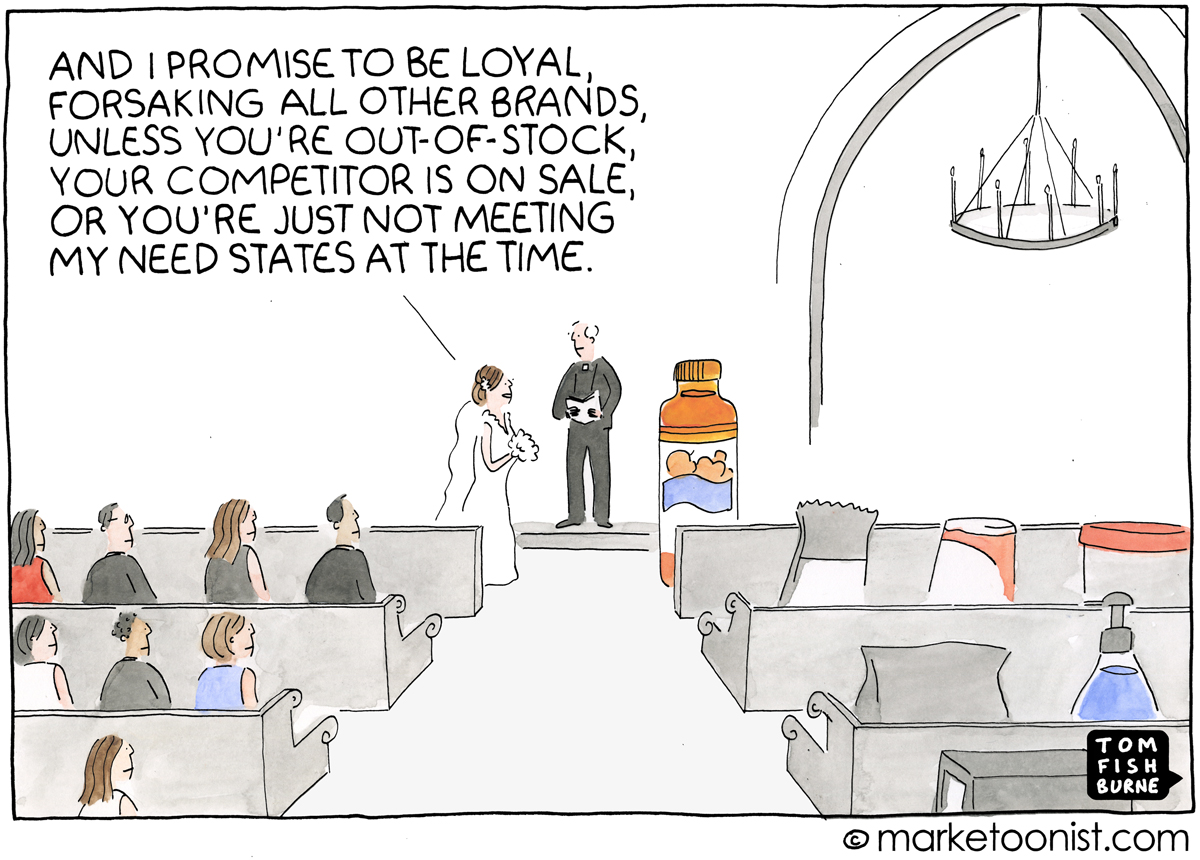

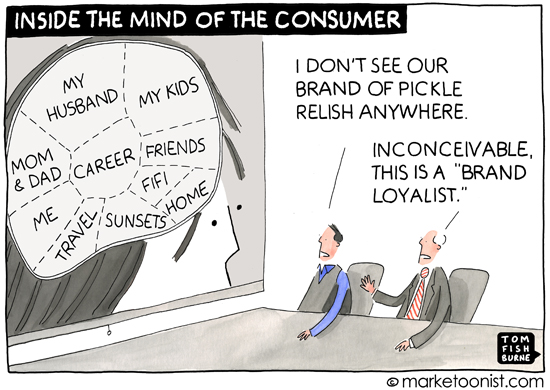

All of this corporate research — shopper decision trees, category management decks, and the like — can be valuable. But followed too closely, they can lead to marketing myopia. Consumers don’t think about brands nearly as much as the marketers of those brands think about the brands.

I’m struck by this classic line from Byron Sharp in “How Brands Grow”:

“Rather than striving for meaningful, perceived differentiation, marketers should seek meaningless distinctiveness. Branding lasts, differentiation doesn’t.”

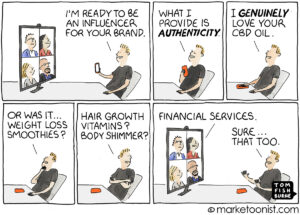

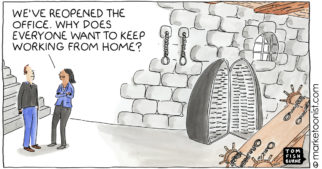

Here are a few related cartoons I’ve drawn over the years: