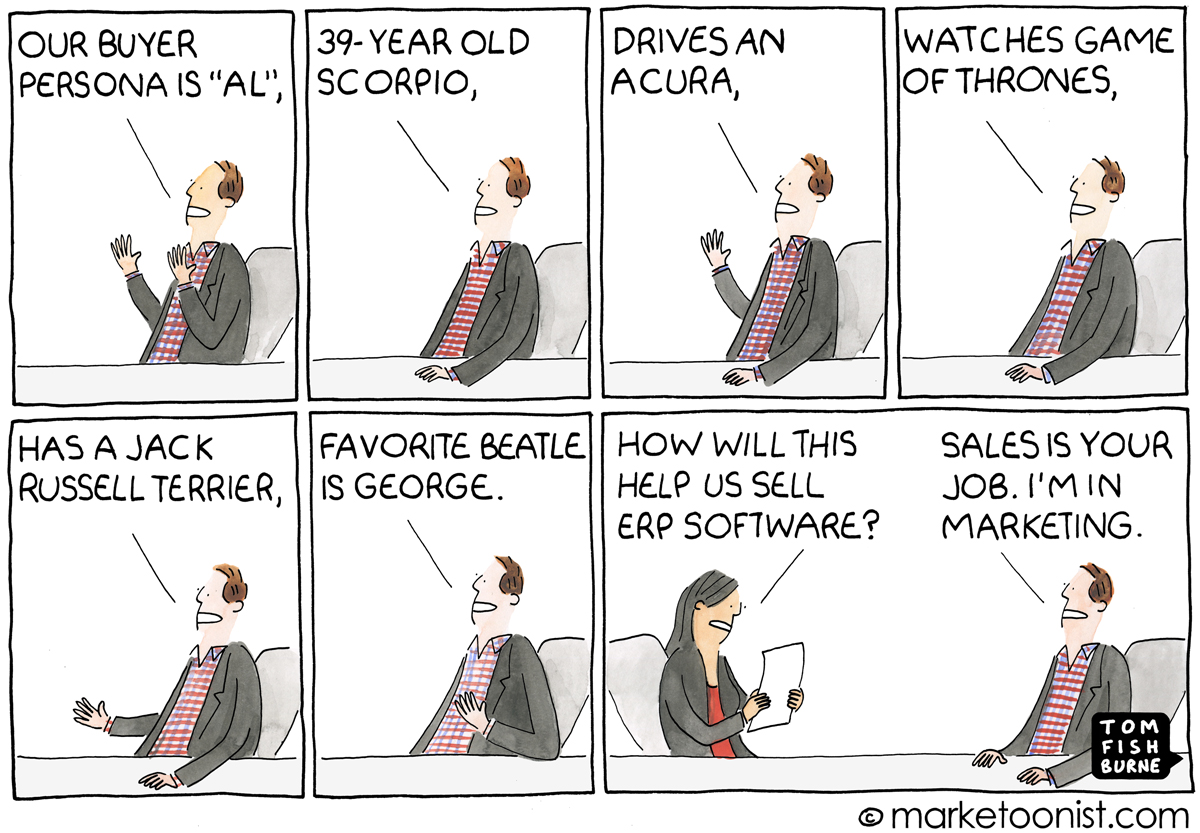

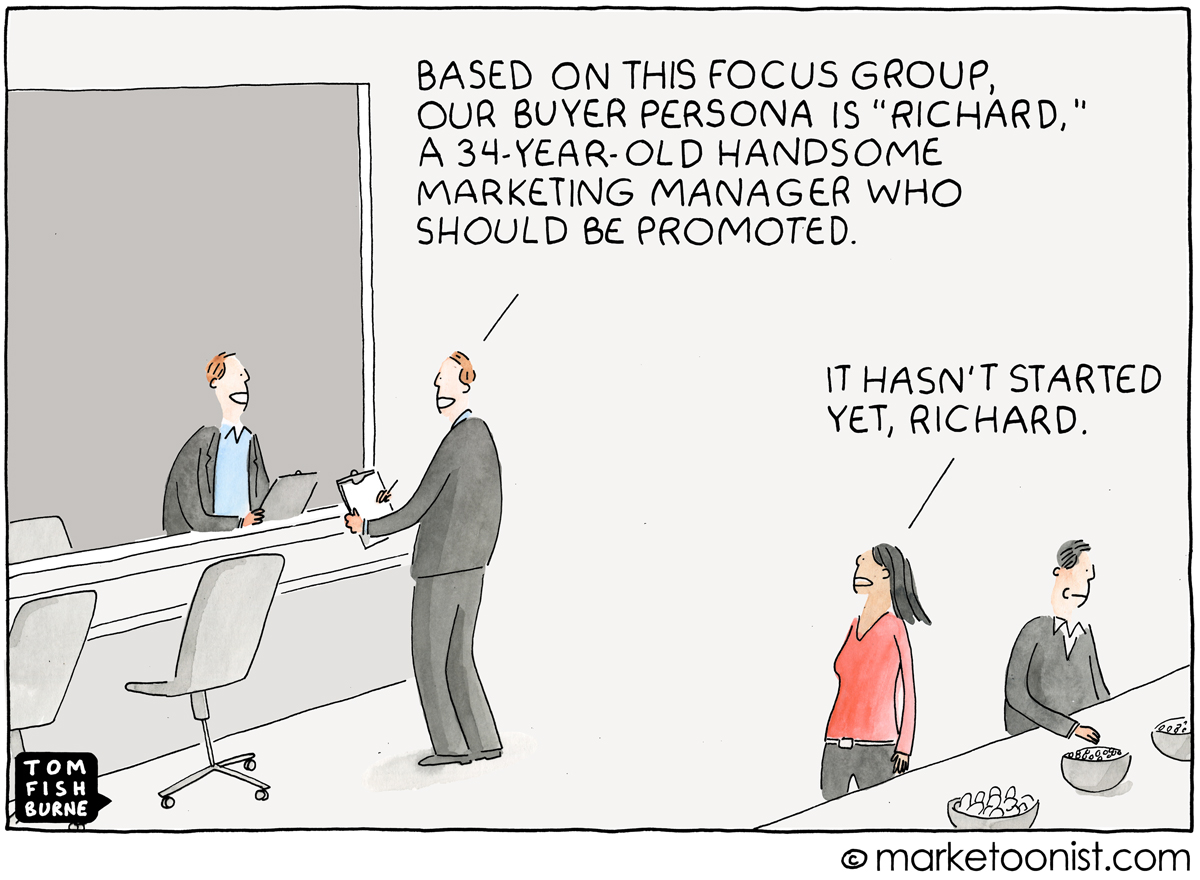

Marketers use personas as a tool to try to bring customers into the room — to help organizations be more customer-centric. They’re intended to help with everything from innovation to experience design to marketing and sales.

At their best, personas can help visualize and communicate insights from research. But at their worst, they have nothing to do with the real world, let alone real people. Personas also often say more about the team that created them than about the customers or users they’re supposed to represent.

One of my favorite professors was Clayton Christensen. I recently re-read his classic 2005 HBR essay on “Marketing Malpractice”, where he skewers some of the flawed thinking in traditional market segmentation (that frequently leads to misguided personas) and introduced his Jobs-To-Be-Done theory.

I find his analysis a refreshing way to think about customer needs:

“The great Harvard marketing professor Theodore Levitt used to tell his students, ‘People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!’ Every marketer we know agrees with Levitt’s insight. Yet these same people segment their markets by type of drill and by price point; they measure market share of drills, not holes; and they benchmark the features and functions of their drill, not their hole, against those of rivals. They then set to work offering more features and functions in the belief that these will translate into better pricing and market share. When marketers do this, they often solve the wrong problems, improving their products in ways that are irrelevant to their customers’ needs.

“Segmenting markets by type of customer is no better. Having sliced business clients into small, medium, and large enterprises—or having shoehorned consumers into age, gender, or lifestyle brackets—marketers busy themselves with trying to understand the needs of representative customers in those segments and then create products that address those needs. The problem is that customers don’t conform their desires to match those of the average consumer in their demographic segment. When marketers design a product to address the needs of a typical customer in a demographically defined segment, therefore, they cannot know whether any specific individual will buy the product—they can only express a likelihood of purchase in probabilistic terms.

“Thus the prevailing methods of segmentation that budding managers learn in business schools and then practice in the marketing departments of good companies are actually a key reason that new product innovation has become a gamble in which the odds of winning are horrifyingly low.

“There is a better way to think about market segmentation and new product innovation. The structure of a market, seen from the customers’ point of view, is very simple: They just need to get things done, as Ted Levitt said. When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them. The marketer’s task is therefore to understand what jobs periodically arise in customers’ lives for which they might hire products the company could make. If a marketer can understand the job, design a product and associated experiences in purchase and use to do that job, and deliver it in a way that reinforces its intended use, then when customers find themselves needing to get that job done, they will hire that product.”

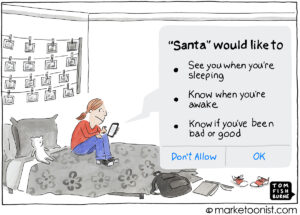

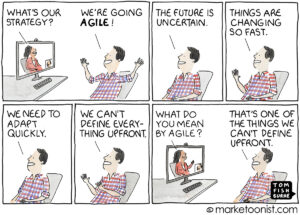

Here are a few related cartoons I’ve drawn over the years: