A Chicago family recently received a promotional mailer from OfficeMax addressed to “Mike Seay/Daughter Killed in Car Crash/Or Current Business.” The Seay family lost their daughter less than a year earlier.

Including “daughter killed in car crash” wording on the envelope was obviously a mistake, but the issue is far bigger than a typo. Having that sensitive data to begin with reveals the inner workings of data brokers and consumer targeting. This is the ugly side of Big Data. Increasing troves of personal data (including sensitive life stage events) are tracked by data brokers to fuel marketing campaigns. Recent Congressional testimony showed that data brokers even sell lists of rape victims and AIDS patients.

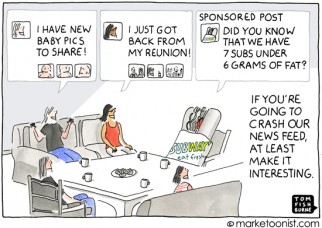

These may be extreme cases, but I think marketers need to clearly draw the line on how they plan to use customer data. In the pursuit of creating relevant advertising, marketers are walking a tricky tightrope on consumer privacy.

Here’s how Macy’s VP of customer strategy, Julie Bernard, framed the issue:

“Consumers are worried about our use of data, but they’re pissed if I don’t deliver relevance… How am I supposed to deliver relevance and magically deliver what they want if I don’t look at the data?”

There’s a legislative movement in the US to limit corporate access to personal data. However government regulation ultimately plays out, I think there’s an opportunity for marketers to take the high road.

As Julie Bernard puts it, “I could just track every phone that came into Macy’s without announcing to people. Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.”

I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences navigating personal data in marketing.

(Marketoonist Monday: I’m giving away a signed print of this week’s cartoon. Just share an insightful comment to this week’s post by 5:00 PST on Monday. Thanks!)

Christoph Trappe says

It’s so useful to get served relevant content when it helps us as consumers.

But there also has to be trust. Think amazon.com for example. The site does a very nice job serving us data (products) that are relevant. I trust them. Mostly because I have not heard a reason why I shouldn’t and because Amazon serves me relevant products.

And of course I signed up for an account voluntarily.

Oana-Maria Pop says

Great post, Tom! The first two things that came to my mind whilst reading were, in fact, two apps. “Whisper” and “Over the Shoulder”. The former: a place to share uncensored comments about everything in your life (including brands, of course); The latter: (I quote) “a tool that provides unprecidented access into consumers everyday lives”. Meaning once installed it will track your journeys during a day and prompt you for feedback (and feelings). While sign-up + consent is required, I imagine it will not take long until major social media sites will integrate this as an embedded feature, making rating (or feedback giving) as well as personal data disclosure mandatory for free service. So another ugly side to Big Data… And it will only get more rude.

Richard Beaumont says

There is much talk of the ‘creepy line’ in marketing, and Google’s Eric Schmidt famously said it was Google policy to get right up to it.

The problem is that where Eric draws the creepy line is very different to where I would for myself.

There is nothing inherently wrong with the practice of consumer targeting of course, the problem in my mind is that it is mostly hidden, and as the example illustrates, the methods can sometimes be highly questionable.

To me the answer of balancing personalisation with privacy is permission. Marketers would do well to be more transparent about what they do, get permission from consumers to do it, and then make sure they get it right – deliver personalisation that does benefit consumers.

This is especially needed online – where every click can be used to build a profile.

There is much talk about consumer ‘engagement’ in marketing circles – but until that engagement starts with permission, it looks to most people a lot like what it is – a euphemism for ‘tracking you as much as possible’.

Darius Kemp says

The question that needs to be asked here is “what EXACTLY am I using this data for?”

As I read the excerpt, I struggle to understand how this family’s tragedy had any relevance to OfficeMax! I’m also confident that the mailer itself did not have any unique content tailored to this family’s particular circumstance.

From my perception, most of this data is simply being used for micro-targeting which is highly inefficient for most businesses.

If your strategy dictates targeting at this level, and you decide to go down the road of purchasing data at this level, then the content and the product should have true relevance to the consumer that you are targeting.

Otherwise, it is at best, an inefficient spend and at worst, a breech of the consumer’s trust and an invasion of their privacy.

Ori Pomerantz says

You need to use data, but not be obvious about it. People don’t have time to think about your ad and try to figure if it abuses their privacy or not. You’re lucky if they notice your ad at all.

Linette Singleton says

Relevance without common sense is fruitless.

Joe Bentzel, Platformula Group says

Another great Marketoon.

Ditto Richard Beaumont’s excellent observations above on the ‘creepy line’ and the rise of non-permissioned marketing.

If marketers want to collect your data, they should pay for it.

They should ‘subscribe’ to the ‘Big Me’, i.e. my lifetime value to them as a customer.

Unfortunately, as long as Wall Street is there in the background looking for the next big ‘marketing technology’ hit, that will never happen.

Concetta says

I think the biggest problem is that they are using the data with no safeguards as to what’s being put out there.

The architectural firm I worked for years ago did a big data project once a year. We would order a list of schools that met the criteria for our firm and then we would go through all the entries, making sure the addresses were correct (at least 10% were usually out of date), making sure the people’s names were spelled correctly (thank you, school district websites!), and generally making sure there was nothing idiotic on them (i.e. women’s names with a Mr., men’s names with a Ms., etc.).

Every time I see one of these mistakes happen like with Mr. Seay’s daughter, I wonder, do people even stop to check these big mailing lists now? Or do they just let them go, assuming the big data companies will do it for them? There’s not a system of checks and balances built into the system to make sure that the data is accurate, appropriate, and ready to go. One hand assumes the other hand is covering the leak in the boat, so to speak.

We as marketers should not have this type of inaccuracy leading to inefficiency, and, as in this case, offensiveness to our potential customers.

Tim Mace says

Marketing without morals. Disgusting but becoming the norm.

Maria says

An interesting and relevant marketoon.

I was fascinated by the Target example Charles Duhigg outlined in his book The Power of Habit. Target’s pregnancy prediction score was effective at identifying pregnant women and triggering coupon mailers – which were sent to a teenage girl. Her father was furious until he had a talk with his daughter and found out, “there’s been some activities in my house I haven’t been completely aware of.”

Target statistician Andrew Pole commented, “We are very conservative about compliance with all privacy laws. But even if you’re following the law, you can do things where people get queasy.”

The new policy mixes coupons for expecting parents randomly with non-baby items. Target found “. . . as long as a pregnant woman thinks she hasn’t been spied on, she’ll use the coupons. She just assumes that everyone else on her block got the same mailer for diapers and cribs. As long as we don’t spook her, it works.”

So, the solution for Target was to avoid being obvious, but not fully transparent / permission based.

The book suggests that Target’s revenue growth went from $44 billion in 2002, when Pole was hired, to $67 billion in 2010 was in part attributable to Pole’s work capturing the expecting parent market.

Is this behavior questionable? I see arguments on both sides.

Sean says

Why should data, like spam and telemarketing, not be an opt-in? Consumers “pissed that you don’t deliver relevance” without having established some direct relationship and data-trust are probably pissed that you are delivering anything unsolicited at all. Blaming data is not a laudable excuse for being a nuisance.