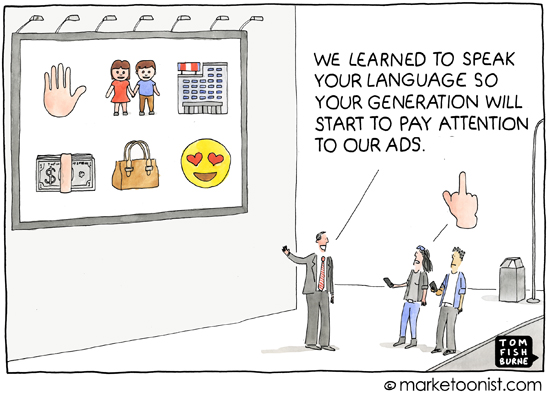

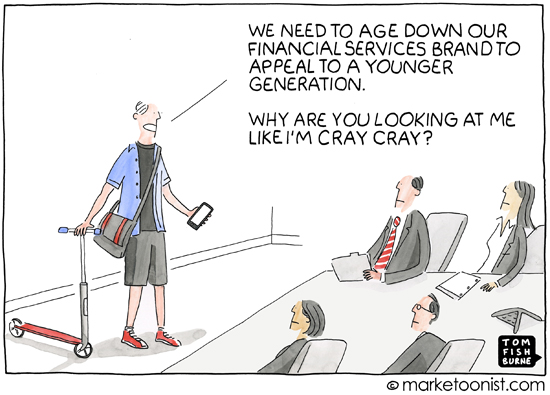

In the 20+ years I’ve been drawing this cartoon series, one evergreen topic I’ve loved exploring is how brands sometimes twist into pretzels trying to appeal to new generations, often with hilarious unintended effects.

Advice often comes in the form of a 5-step checklist — or a “one weird trick” — that magically promises to make brands appealing to the newest customer cohort (whether Millennials, Gen Z or, most recently, Gen Alpha).

Last year, Edelman, the world’s largest PR firm, opened up a Gen Z lab and hired a “ZEO” to run it. One piece of advice from their ZEO quoted recently in the Guardian: “Don’t make some weird old-ass campaign.”

This is nothing new. There’s a clear through line from the “Not your Father’s Oldsmobile” campaign of 1988 to the “Not your Mother’s Tiffany” campaign of 2021.

Trying to stay relevant for the times without losing what the brand stands for is a fundamental age-old tension.

I was recently asked to speak at the ad:tech conference in New Delhi in March on the topic of “how brands should re-invest themselves for Gen Z.”

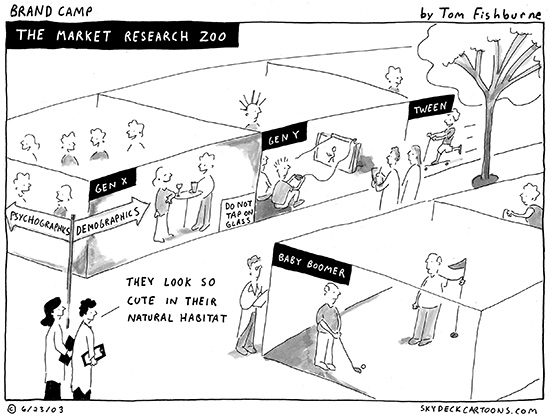

The invitation has gotten me thinking about some of the myths of generational marketing in general. Generations are often described in monolithic terms, like a separate species with uniform characteristics.

BBH Labs measures “Group Cohesion Scores” and found that “people who floss” had more in common with each other that any generation.

Pew Research Center, a pioneer in generational research, recently re-evaluated how they use generational labels entirely.

As Pew’s director of social trends research, Kim Parker, put it:

“The question isn’t whether young adults today are different from middle-aged or older adults today. The question is whether young adults today are different from young adults at some specific point in the past …

“As many critics of generational research point out, there is a great diversity of thought, experience, and behavior within generations. The key is to pick a lens that’s most appropriate for the research question that’s being studied …

“By choosing not to use the standard generational labels when they’re not appropriate, we can avoid reinforcing harmful stereotypes or oversimplifying people’s complex lived experiences.”

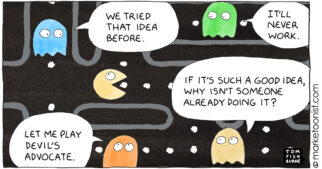

I like the idea of picking a “lens that’s most appropriate.” The choice of lens will be different for different brands with different goals.

Brands have to continually re-invest to stay current and relevant and meaningful for a continually evolving mix of consumers. But they also have to be careful not to treat generations as monoliths.

Here are a few related cartoons I’ve drawn over the years (including one from 2003!):